In the last two decades, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have uncovered many thousands of associations between genetic variants and a wide array of phenotypes. While much has been learned from this work, an ongoing and pressing challenge is understanding the biological mechanisms that underlie these signals, most of which fall in non-coding regions of the genome.

Most of my work so far has focused on addressing this key question by exploring statistical interactions between genetic variants. Such interactions – where the combined effect of two variants on a phenotype is different from the sum of their effects when present in isolation, known as ‘epistasis’ – can shed light on biological mechanisms by pointing to functional interactions between parts of the genome whose effects on a phenotype are found to be statistically interdependent. However, the detection of interactions has been hampered by various statistical and computational challenges. In my work to date, I have focused both on methodological developments to circumvent these obstacles as well as on identifying novel interactions.

Beyond genetic interactions, I have broad interests in statistical and population genetics and have also contributed to research on measures of fine-scale ancestry, differences in genetic effects across population groups, and the genetics of disease. Please see the papers below for more details.

Ferreira, L.A.F., Hu, S., Myers, S.R. Interactions with polygenic background impact quantitative traits in the UK Biobank. medRxiv (2025).

The primary obstacle to the detection of genetic interactions is the vast search space to cover which, for pairwise interactions, is in the order of the square of the number of variants considered. To increase statistical power, in my PhD project we developed a test for interactions between single-nucleotide variants (SNPs) and groups of other variants aggregated into a polygenic score (PGS).

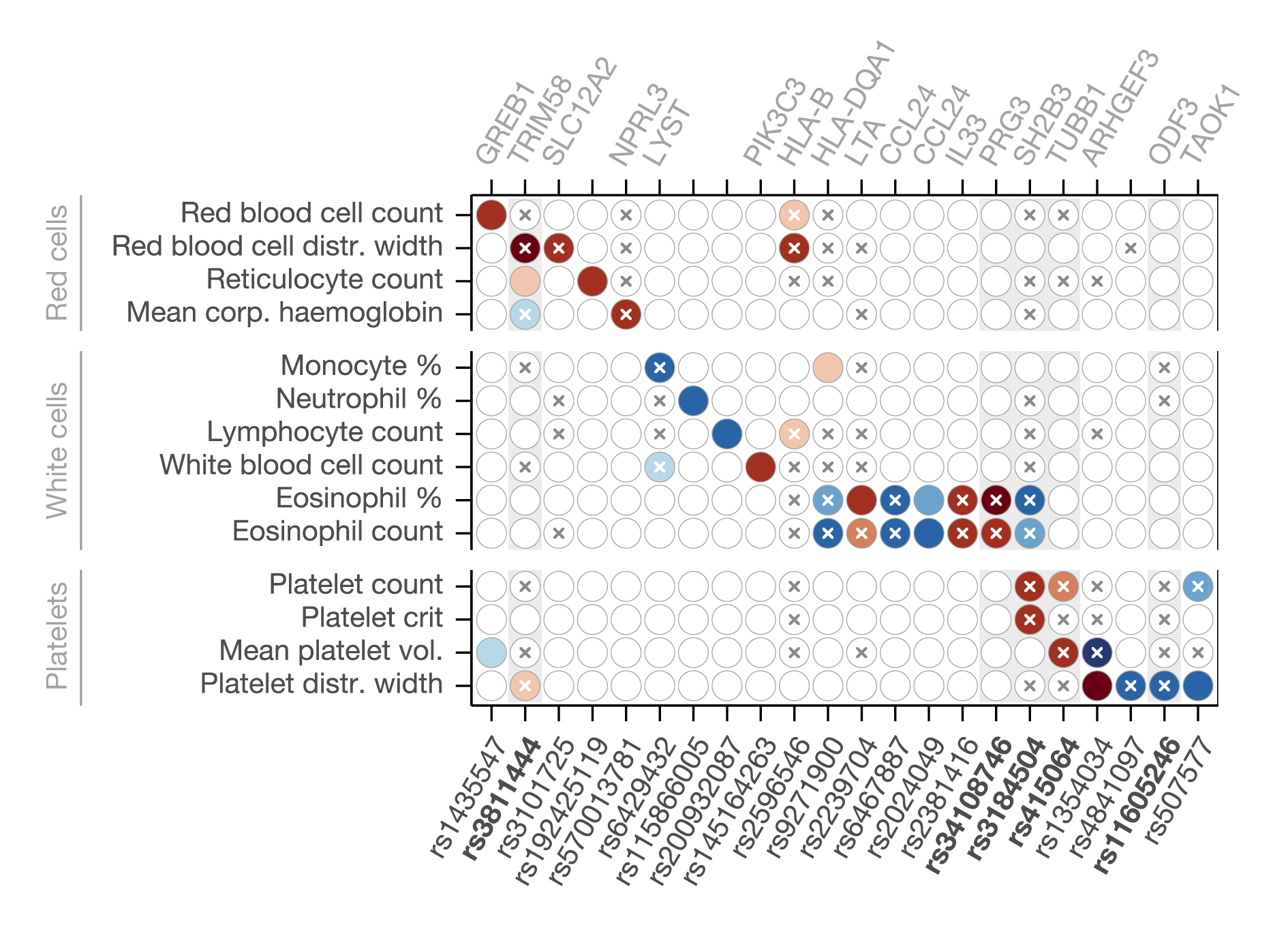

We applied this method to 97 quantitative traits in the UK Biobank, identifying 144 interactions with PGSs for 52 different phenotypes. These include well-known disease risk variants at APOE, FTO and TCF7L2. In addition to these interactions with polygenic background, we also uncovered 38 interactions between pairs of SNPs, of which 32 are novel. One highlight from these results is an interaction between ALOX15 and IL33 affecting eosinophil levels that could reflect a recently reported functional interaction between these two genes implicated in eosinophilic asthma.

We refined the interactions between SNPs and polygenic background identified above by partitioning PGSs using transcription factor (TF) binding motifs. Testing for interactions between loci previously found to interact with a PGS and small components of that PGS defined using this data revealed 12 novel interactions with TF-specific scores. A highlight is an interaction between TCF7L2 (a key regulator of glucose metabolism and important diabetes risk locus) and KDM2A for glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, two TFs which have been found to interact physically within the Wnt signalling pathway.

Hu, S., Ferreira, L.A.F., Shi, S., Hellenthal, G.,* Marchini, J.,* Lawson, D.J,* Myers, S.R.* Fine-scale population structure and widespread conservation of genetic effect sizes between human groups across traits. Nat. Genet. 57, 379–389 (2025).

A second major challenge facing human genetics is the limited applicability of genetic findings – and in particular of genetics-based disease risk prediction models (PGSs) – to individuals of non-European ancestry. Driven by the strong bias towards European populations in genetic data collection and subsequent analyses, these limitations risk exacerbating existing inequalities in access to healthcare as genomic medicine becomes a reality.

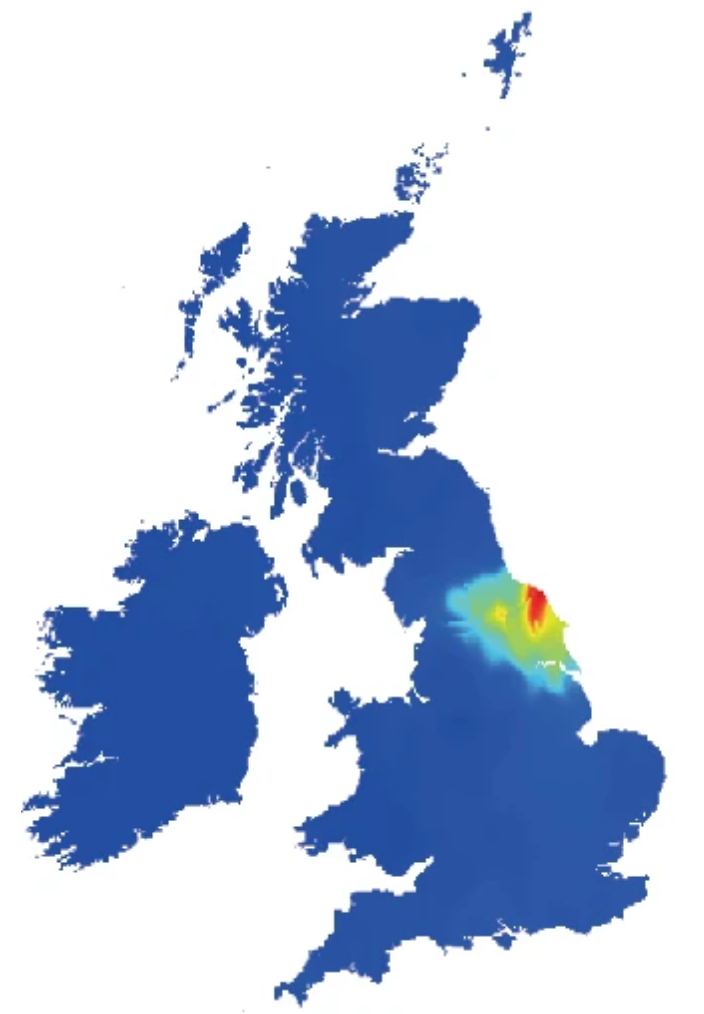

In this paper, we investigated the genetic differences between populations that underlie this lack of transferability. We first proposed a new method to partition an individual’s ancestry into geographically meaningful components pertaining to 127 population groups, which we show enables better correction for fine-scale population stratification than existing methods. We then developed a novel approach to estimate the correlation in causal effect sizes across populations using data from admixed individuals. An application to the UK Biobank found effect sizes to be highly correlated between European and African ancestries and thus points to other factors as underlying the limited transferability of PGSs. My contributions were in the analysis of simulated data and in comparing its performance with other state-of-the-art methods for real phenotypes.

Ignatieva, A., Ferreira, L.A.F. Phantom epistasis through the lens of genealogies Genetics (2025).

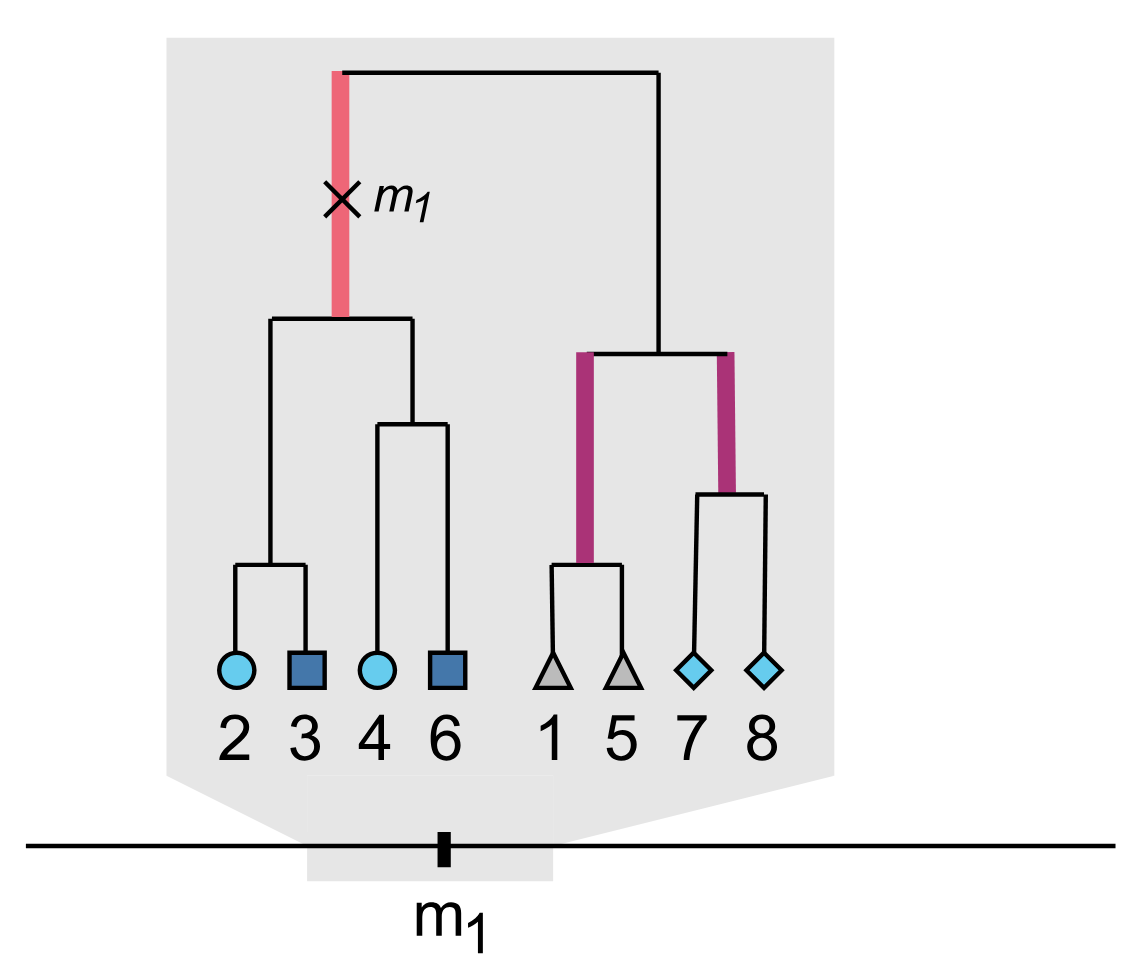

An important statistical challenge when testing for genetic interactions is that a purported interaction between two variants can sometimes be caused by the additive effect of an unobserved and correlated third variant (‘phantom epistasis’). Such false-positive findings of interdependence between two genetic loci are more likely to arise when these are in close proximity and so, even though genetic interactions between neighbouring loci could be commonplace and represent an underexplored dimension of genetic association, there was no reliable way of testing for this potential confounder which has led to false-positive inferences in the past.

We proposed a method that uses reconstructed genealogies in the form of ancestral recombination graphs to quantify the evidence for and against phantom epistasis for a given interaction. Our approach only requires publicly available data and is available as an open-source software package (Spectre: Searching for Phantom EpistatiC interactions using TREes). I was involved in this project from its conception, making significant contributions to the development of statistical methodology and the writing of the paper.